Sarah Newby was 21 when her father, P.H. Newby, won the first Booker Prize for his novel Something to Answer For. She recalls, fifty years later, the award ceremony at Drapers Hall on 22 April, 1969:

My father told us as soon as he knew he’d been shortlisted. He just said, “Unbelievably, I’ve been short listed for the Booker McConnell prize,” as it was then. And I didn’t know what that was, and he explained that it was a prize of money authorised by a company that dealt a lot with sugar. He was worried about accepting the prize, because the company had originally made their money through the slave trade. But he overcame his scruples, because it was a large sum of money in those days, and we weren’t that well off, and he didn’t make an awful lot from his writing and he knew that this would boost his income outside the actual prize itself.

He told us he’d won in the car on the way to the ceremony, because he needed to explain what would happen; he would be taken away to do interviews and things, and we would have to hang around in the hall to wait for him. He said, “You mustn’t say anything to anybody at the dinner, but I have actually won.”

I think he was a bit overwhelmed. And I don’t know how long he’d known, but he was also slightly embarrassed. He was a shy man and knowing that he got to do all these interviews, worried him. The funny thing was, once we were in Drapers Hall, where the dinner was held, I went in to the ladies and people were putting bets on who would win, and I had to keep quiet. I could have made a lot of money if I’d wanted to. Somebody was running a betting ring.

My mother was delighted that he’d been shortlisted. She bought a new outfit. She couldn’t afford the sort of clothes that she would have liked, so she found a dressmaker, and she had dresses made in various fashions with lovely material, so she always had something that nobody else would be wearing. I’m sure that’s what she did for that occasion. She loved dinners and parties and things like that. It was so different from her childhood and growing up; suddenly to be going to these occasions was very exciting for her.

They were both working class. My father had had a very itinerant upbringing, because his father was a baker who moved around all the time and they were in Wales for a while. And then they were down in Sussex and then ended up in Wendover, Buckinghamshire. But he went to so many different schools. He went to school in Wales, where everything was taught in Welsh. It was a great disadvantage for him.

He took his exams and he did very well. And his stepmother very much wanted him to go to university, but in those days, there were no grants and they just couldn’t afford it. But he did get a place at teacher training college, which I think had money attached to it – well, he got a sort of scholarship or something – and he taught for a while before he joined the army.

I was studying in London, but I think I was still living at home at that point. I remember my father gave me £18, which was an awful lot of money for me, to go and buy something special to wear. And I think at that stage, he must have known he’d won. And that was lovely. I went and bought things that I would not normally be able to afford. I bought a gold knitted mini dress, and sparkly tights. It was a bit over the top, but I liked it anyway.

When we arrived, Drapers Hall was like any of these halls belonging to different trades. It was quite grand, and I remember it was set out with round tables. I can’t remember who we sat with. Most of the people who were there were writers or publishers or agents. I can’t remember the food at all. I think I was just so excited and I’m sure it was delicious, but I can’t remember.

I think my father had a glass of wine, but he knew he mustn’t … We shouldn’t overdo it, which was difficult for him, because usually if he was making a speech or doing something live, he used to drink quite a bit to give him courage. But on that occasion, I’m sure he didn’t.

After dinner, Dame Rebecca West announced the winner. There was a lot of applause and an explosion of chatting. “Have you read it?” and things like that. He wasn’t expected to win. I just sat there feeling very smug, with a big smile on my face.

My father made a thank you speech, which wasn’t very long. I mean, he’d had a chance to prepare it obviously. He was a good speaker, so I think it was amusing. People laughed. He talked about the difficulties of being a weekend writer, and about previous prizes he’d won, but said that this was the best. And he was very honoured.

I can’t remember if he mentioned my mother, but I’m sure he did because she put up with a lot really. He didn’t drive, so she had to drive him everywhere he wanted to go, and she was very patient at weekends, and just put with feeding him at mealtimes. I was still at home so obviously I was company for her, but I was often out weekends, so she was on her own then. And we had Katie of course [Newby’s other daughter, five at the time].

After my father finished his speech he was rushed off – there was this live broadcast to Australia. He was probably talking to other people after that as well. I mean, we weren’t seeing what he was doing. We were just sitting, enjoying finishing our wine and chatting to various people who came up and congratulated us. And not really knowing what to do next.

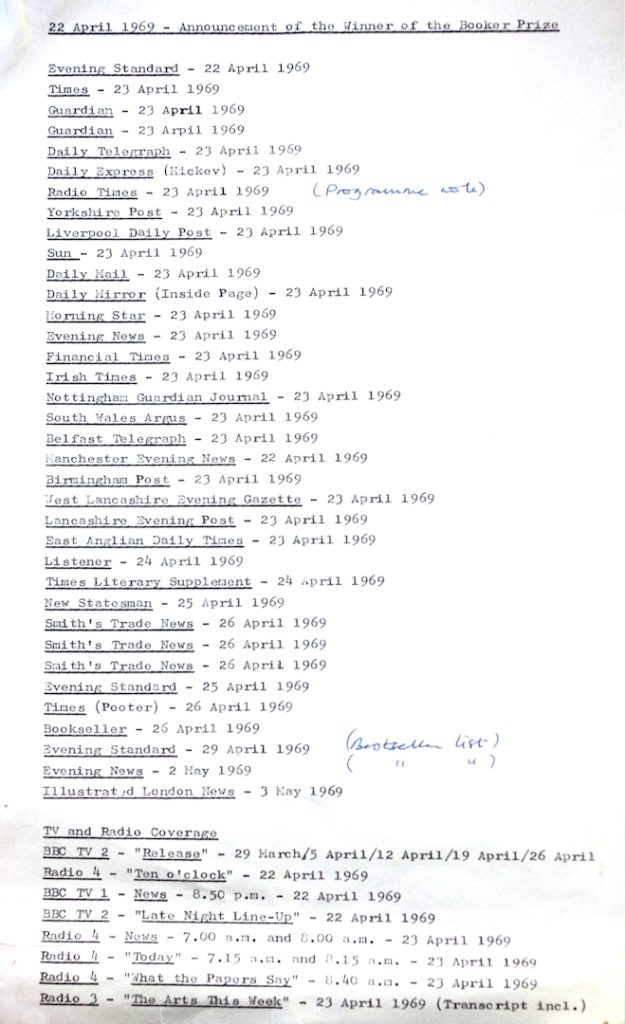

Eventually my father came back. And then we went off. My memory is that we went straight to BBC Television Centre, for a live chat show, a late night one obviously [“Late Night Line-Up” on BBC Two]

We stayed in the reception area at television centre, and we watched the interview later. I can’t remember if it was that night or another night, probably another night. I can’t even remember if we had video recorders then. Maybe they gave us a tape. I think my father was sort of slightly on a high by the time of that interview. I would imagine he’d had a couple more drinks, and he was expansive and entertaining.

A television crew came to film us a few weeks before the prize [part of the programme “Release,” broadcast on BBC Two, 19 April, 1969]. There weren’t very many of them. I think it was just one camera, a sound person, and the interviewer. It was very exciting. We were all rather nervous but somebody directed us so we knew what we’d got to do. My mother had to take something out of the fridge, and she had to do it about three times to get it right. And I had to sit down in a chair and look and start to read a book. Afterwards, I realised I’d got it upside down.

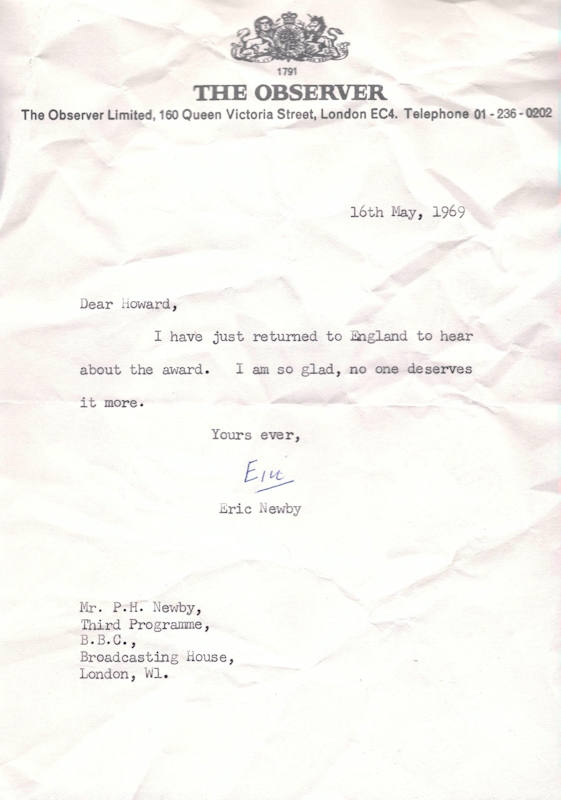

He did a lot of interviews in the weeks following the win, because there was a lot of interest from America. And his books have been translated a lot of times. I think various European countries interviewed him too.

There was all the fuss in the bookshops, because nearly all the big bookshops did displays, and they used replicas of the statue that he’d been given. They put them in the window, surrounded by piles of his books. My mother took one of the replicas. She just approached a book shop and asked to pick it up after they had finished with it.

I can’t remember what my parents did with the trophies, the real one and the replica, at that time. But when they later moved, one was in the bathroom with a plant on it and I think the other one was in the hall, also with a plant on it. They framed the cheque and put it in the downstairs loo, and the trophy went in the upstairs bathroom.

Sometime later my mother spray-painted both trophies gold. My father wasn’t bothered. She just thought it would look better. And then later, when they lived in Garsington, one of the trophies went by the front door and was used to put keys in.

My father had a study upstairs. It was one of the bedrooms, and he would just disappear after breakfast, then appear for lunch. Disappear again and then in the evening, he would be in the kitchen eating his supper, and listening to the Third Programme, as he did every evening, to make sure everything was all right. And occasionally, he made angry phone calls to Broadcasting House, because of something that had been said; or to comment on the music that was being played; or such and such needed explaining to the public, and things like that.

My mother just thought he was very clever. I mean, some of the novels were about things she recognised, that she knew about. I think she did go on a picnic to Sakkara some point, but the book is set earlier than that [The Picnic at Sakkara was published in 1955. It was adapted for television in 1959].

In Egypt they lived in a flat and they had a servant which was very strange for my mother, because her mother and all her aunts had been servants. So, she found it very difficult having to tell somebody what they wanted for lunch and things. And she horrified my father by going out on buses around Cairo, wearing trousers; she’d got used to wearing trousers in the war and she found them comfortable and practical, but he had to ask her to stop it because she could have got into trouble.

It was 1956 and he was in Port Said. About these two facts Townrow was reasonably certain. He had been summoned there, to Egypt, by the widow of his deceased friend, Elie Khoury. Having been found dead in the street, she is convinced he was murdered, but nobody seems to agree with her. What of Leah Strauss, the mistress? And of the invading British paratroops? Only an Englishman, surely, would take for granted that the British would have behaved themselves. In this weirdly disorientating world, Townrow is forced towards a re-examination of the basic rules by which he has been living his life; and into a realization that he too may have something to answer for.